Had GM produced the Lean Machine, we'd now be able to drive the ultimate self-isolation vehicle

GM Lean Machine. Photo courtesy GM Media.

Frank Winchell never liked the name “Lean Machine,” as GM called the three-wheeled concept vehicle that it showed off in 1982. To him, it was the cambering vehicle, nothing more. Yet the name, an obvious pun on its tilting nature, also connoted the efficiency that Winchell strove for with the “only revolutionary new road vehicle developed this century,” as GM described it.

In his 42 years at GM, Winchell not only rose to become the company’s vice president of engineering, he also gained the respect and admiration of David E. Davis and John DeLorean, the latter of whom said Winchell was “as important in the development of the modern racing car as Colin Chapman” due to his work with Jim Hall on aerodynamic improvements to race cars.

From his work on tank transmissions for GM’s Allison division during World War II, to his attempts to get GM to build more Mini-like vehicles with front-wheel drive and transverse engines during the Sixties, to his defense of the Chevrolet Corvair, Winchell had a momentous career with GM, and he had hoped that his last major innovation, what became the Lean Machine, would have radically altered the American automotive landscape.

The idea for his cambering vehicle came, according to his grandson Nick Gigante and according to Winchell himself in a number of contemporary interviews, from the fuel crisis of 1973. At the time, Winchell looked at the cars that Americans drove and reasoned there was a “real need for a single occupant vehicle – one that’s really efficient, very lightweight, has very little aerodynamic drag, and gets good fuel economy.”

Winchell wasn’t alone in coming to that conclusion, but his solution was rather unique. With a single occupant, he reasoned the vehicle should be narrow enough to ride two-abreast in a single lane “to make a nice, neat hole in the atmosphere.” But to give a narrow vehicle any sort of lateral stability, he figured it had to lean or camber into corners, pointing to how humans and animals managed weight transfer by leaning into a turn while running.

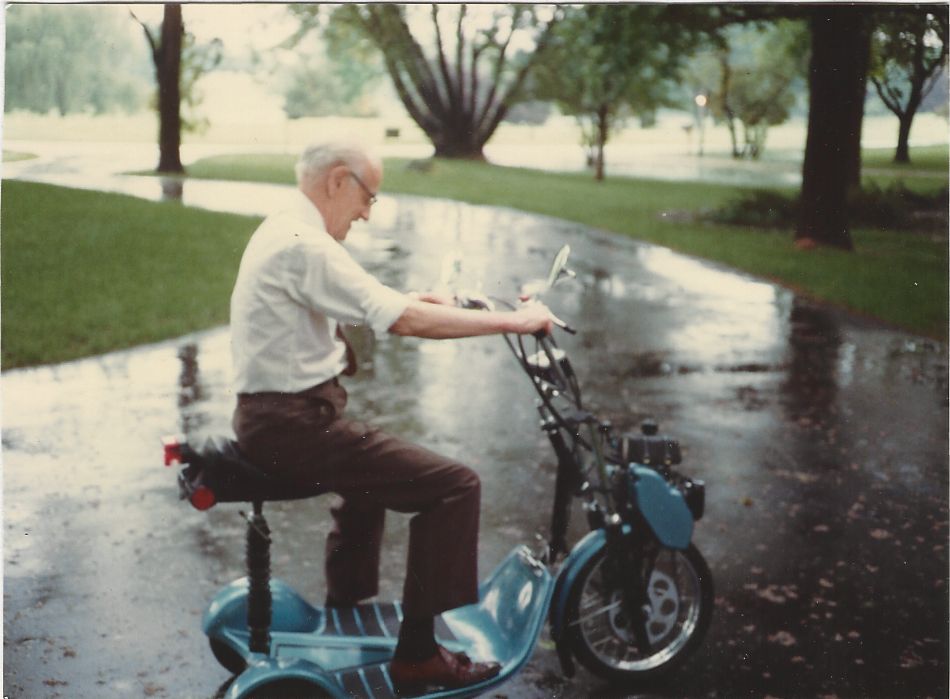

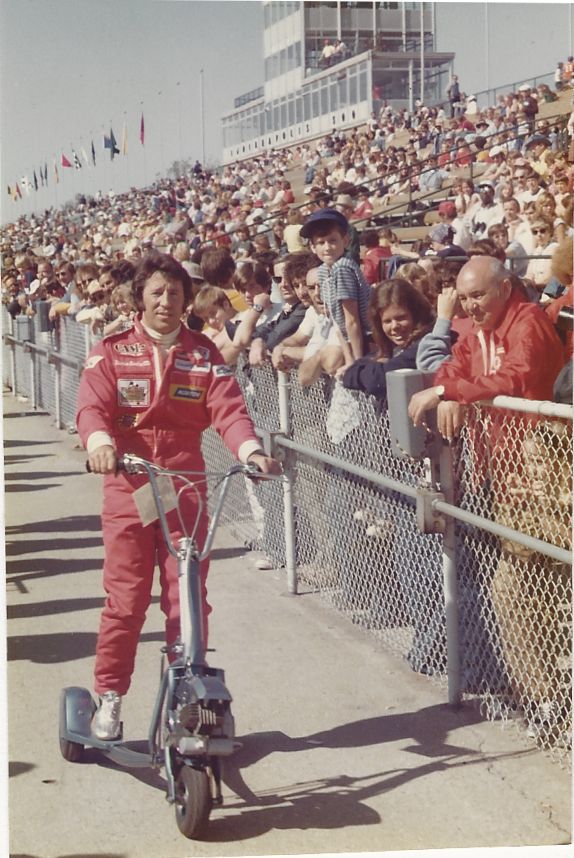

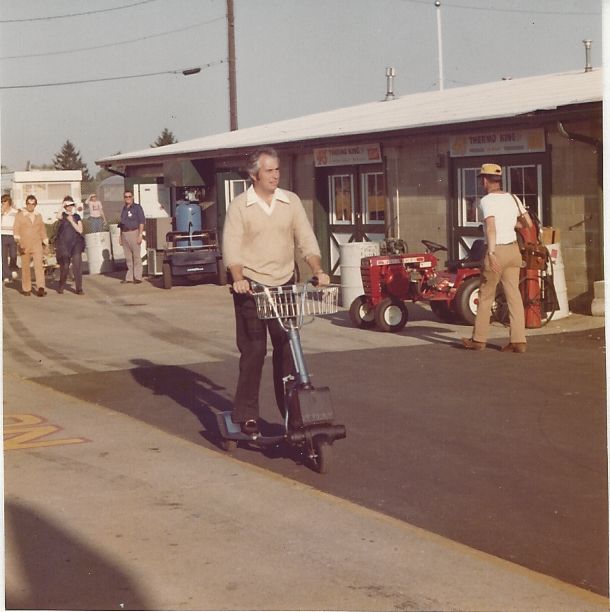

Photo courtesy Nick Gigante.

So starting in the mid-Seventies Winchell pulled together a small team of engineers to build a series of compact tilting three-wheelers. He started with a basic unpowered scooter with one wheel fore and two aft, all linked to allow tilting into corners.

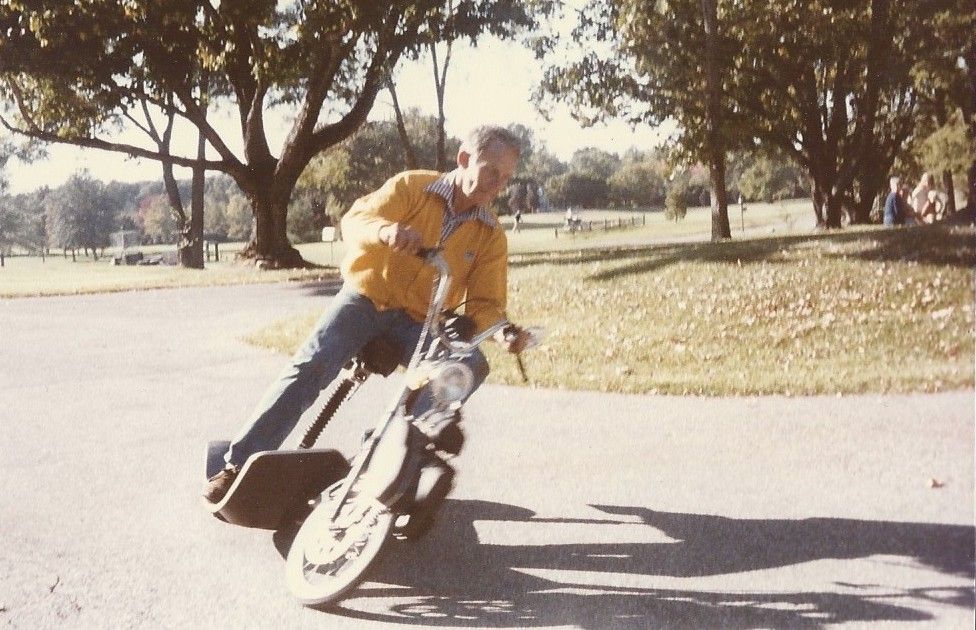

Photos courtesy Nick Gigante.

After that proved workable, he and his group – including project manager Jerry Williams, draftsman Clark Irwin, and fabricators Darrel Landmesser and Ken Whitelam, according to Peter Egan’s account of the Lean Machine in the January 1983 issue of Road and Track – then progressed to powered scooters, both with and without seats. Some looked like early versions of today’s mobility scooters, just with gas engines powering the front wheel and far better cornering capacity. That’s Winchell in the leather jacket, by the way.

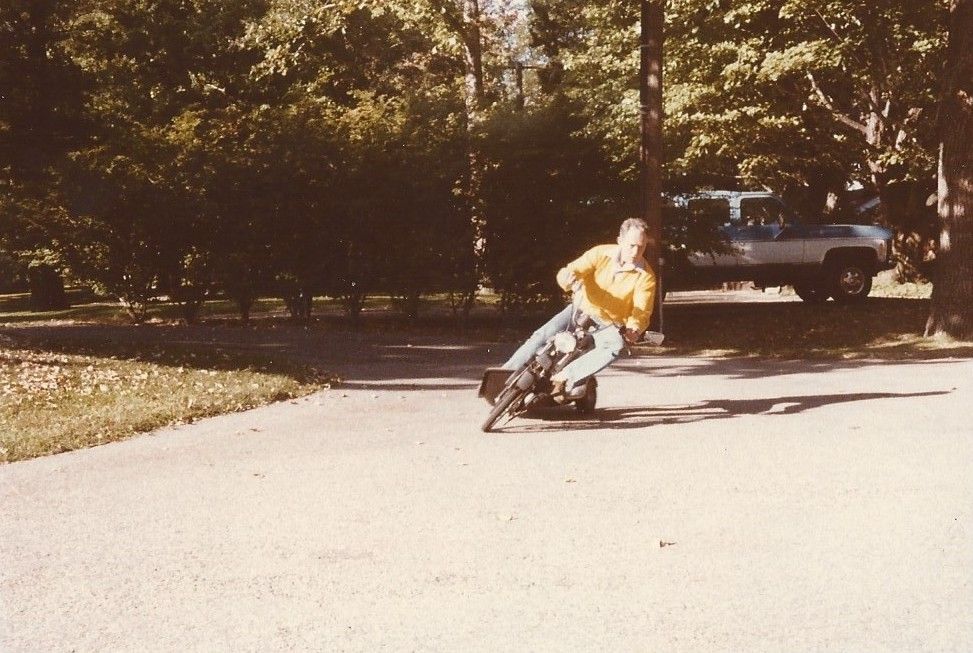

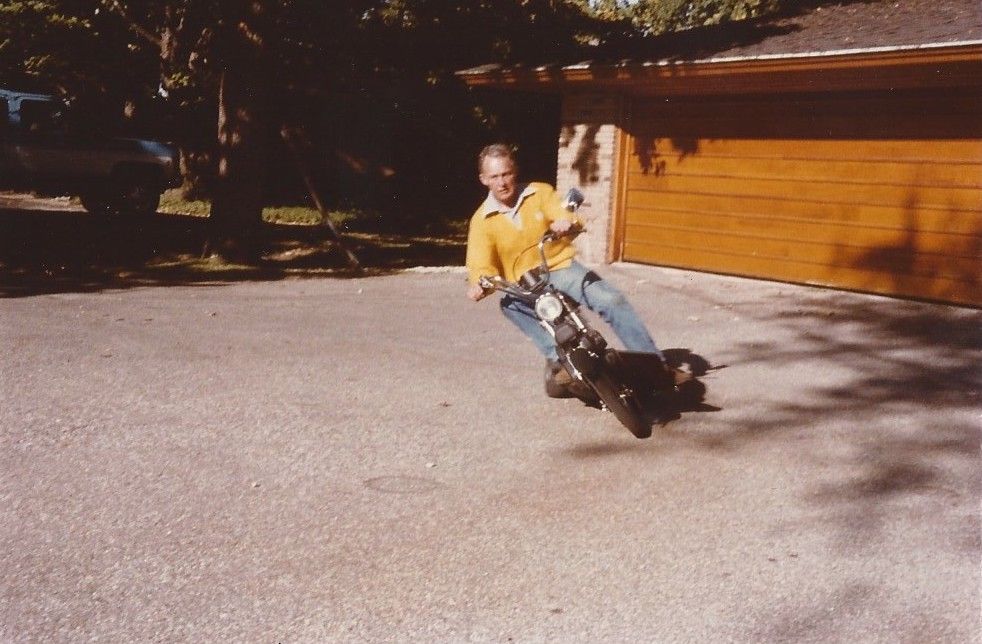

Photos courtesy Nick Gigante.

Unsurprisingly, the fun little powered scooters got a lot of use, from Winchell himself to Mario Andretti to Roger Penske to Tom Sneva.

Photos courtesy Nick Gigante.

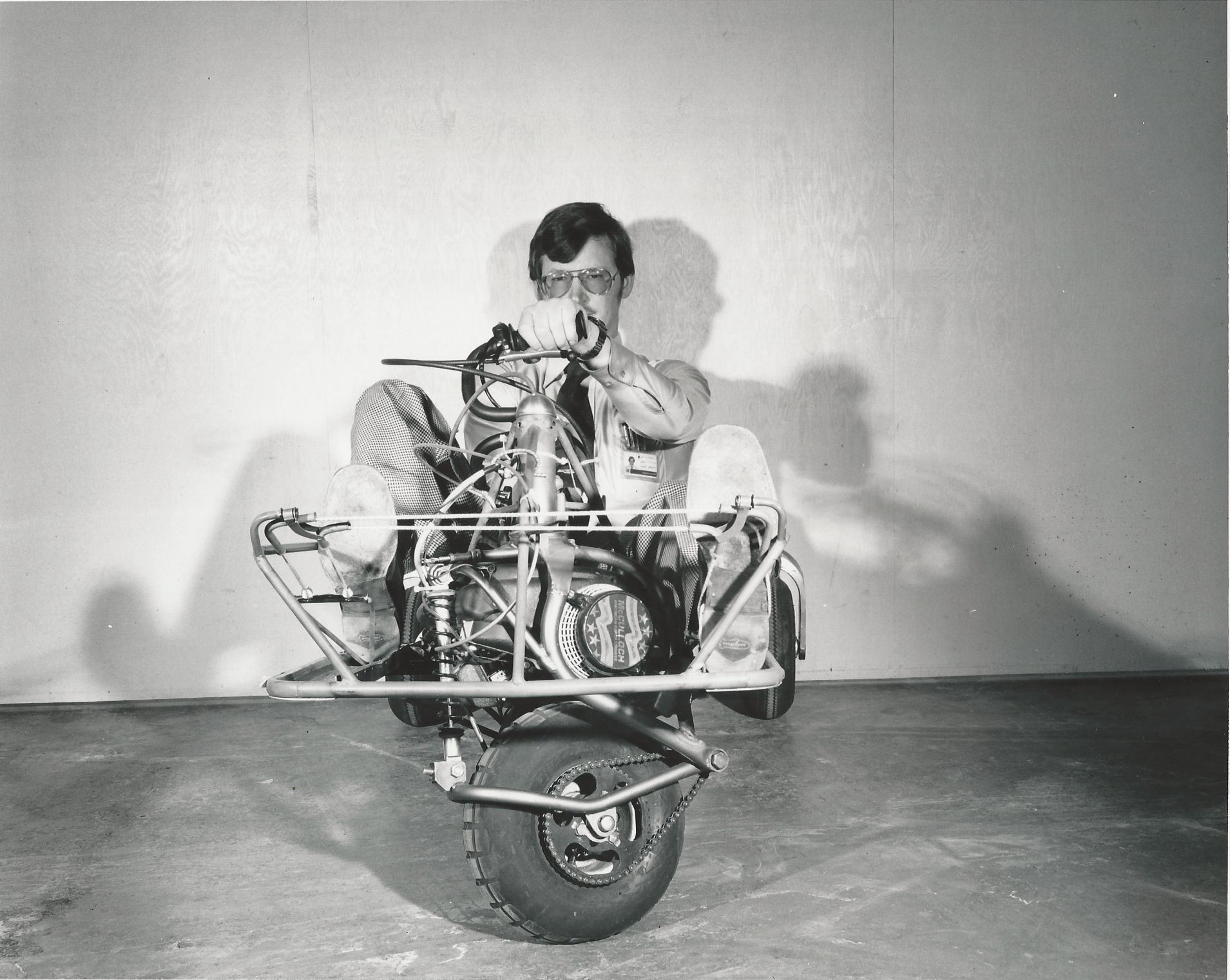

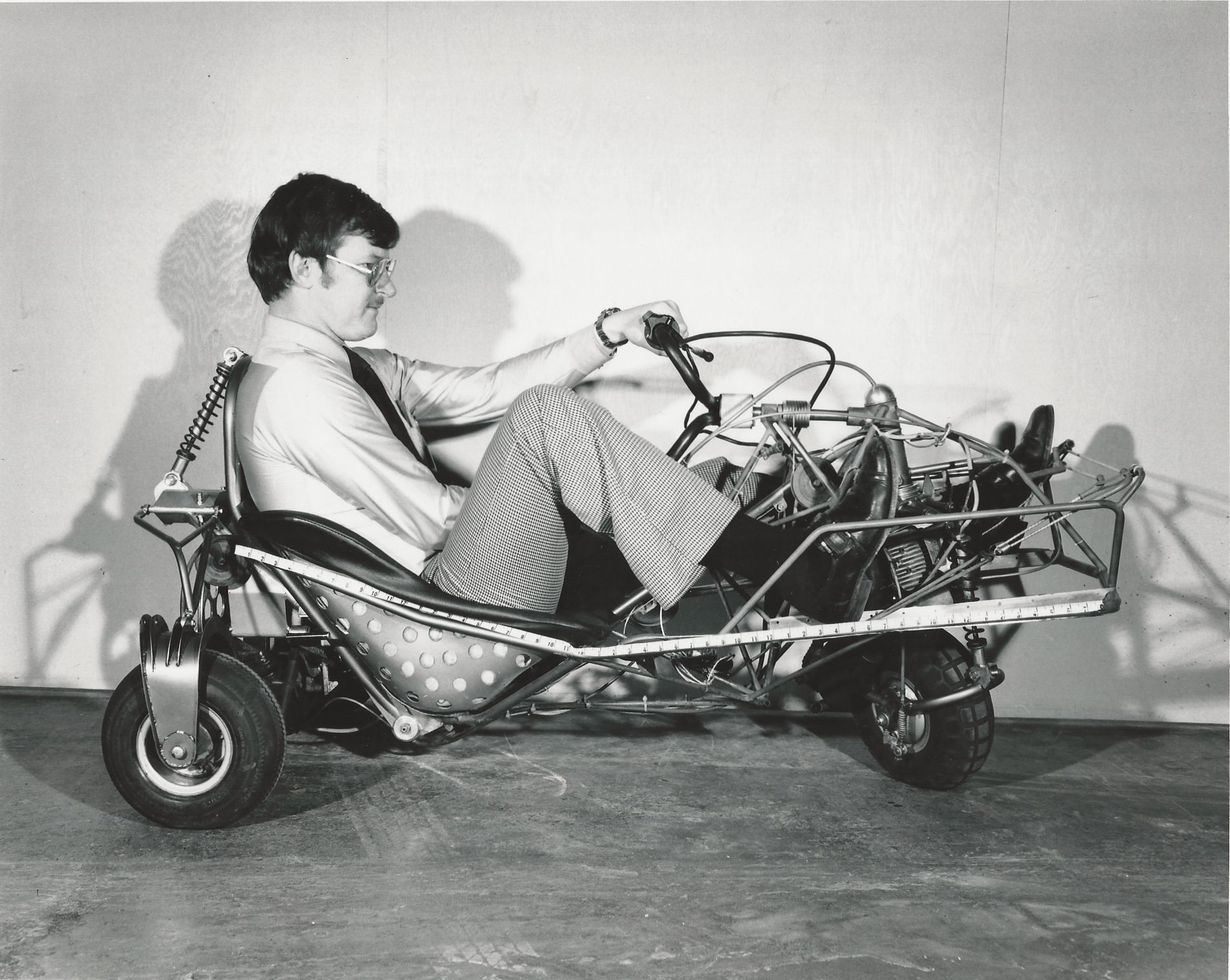

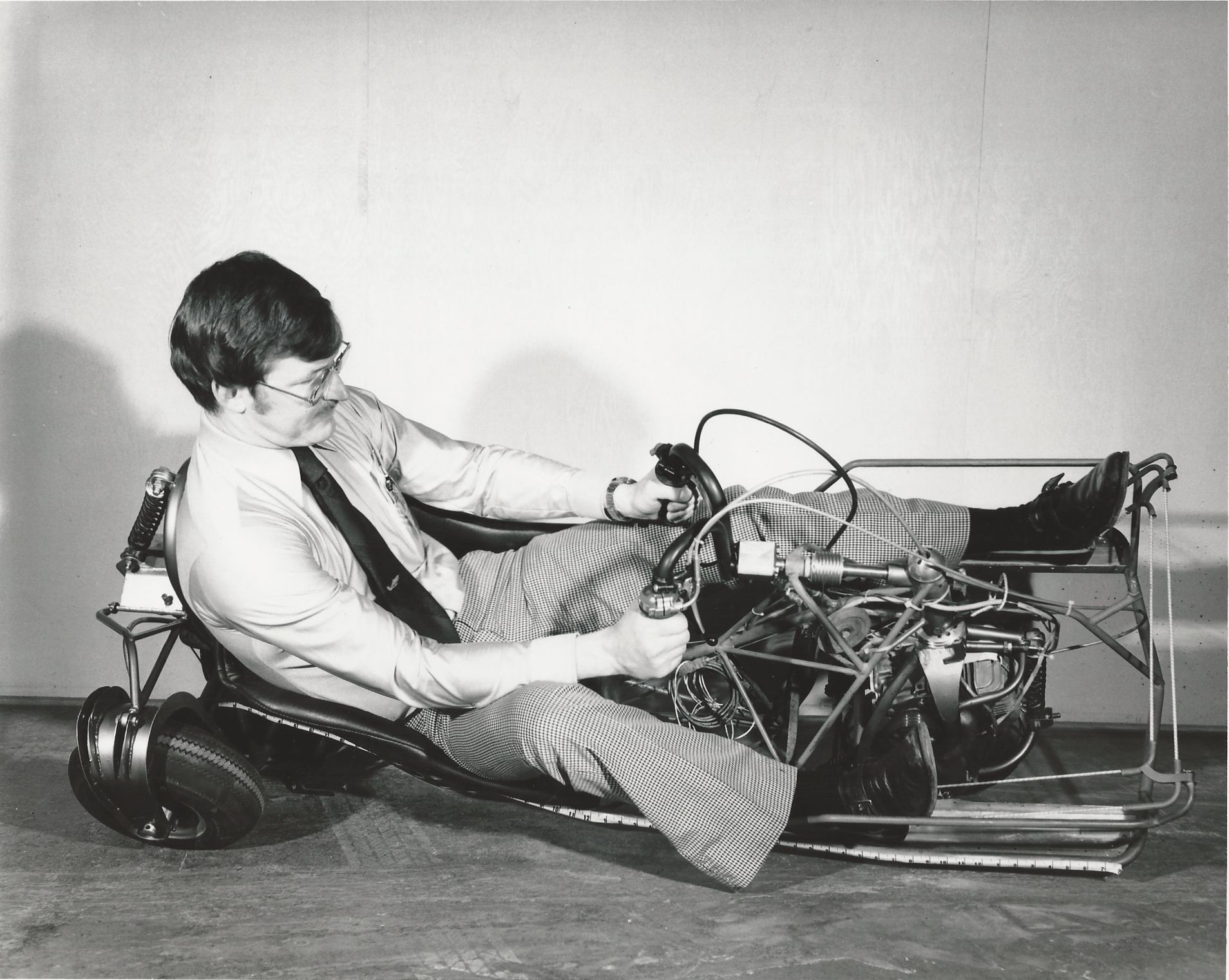

Winchell, however, wasn’t aiming for a toy or a pit bike replacement. To achieve his goal of a fuel-efficient and aerodynamic commuter vehicle, he needed to have the driver recline rather than stand up, resulting in this odd contraption. While it remains front-wheel drive, courtesy of what appears to be a McCulloch chainsaw engine and a motorcycle chain to the front wheel, Winchell also decided to have the driver’s feet control the vehicle’s tilt via cables and pulleys rather than rely on gyroscopes or computer controls.

Photo courtesy Nick Gigante.

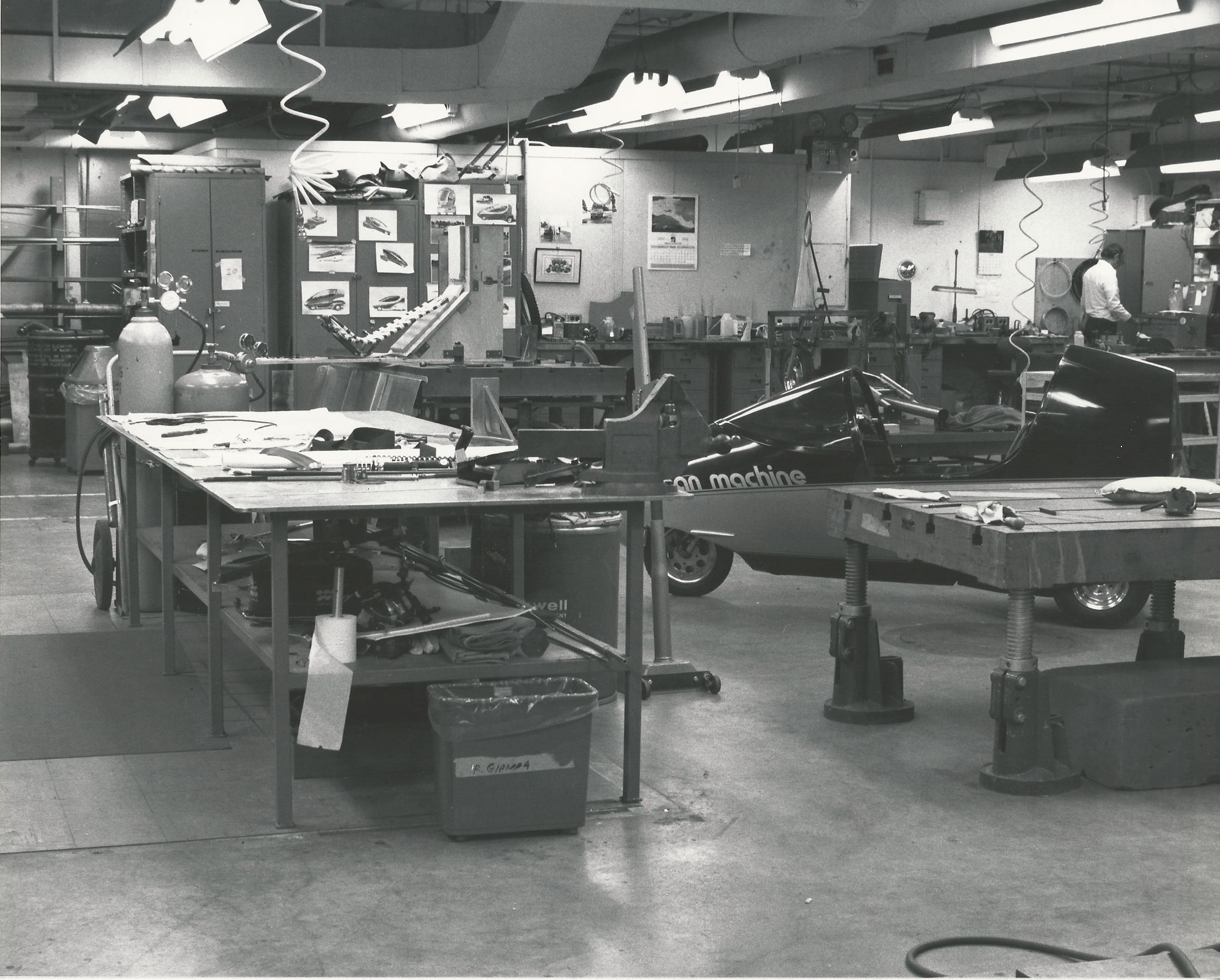

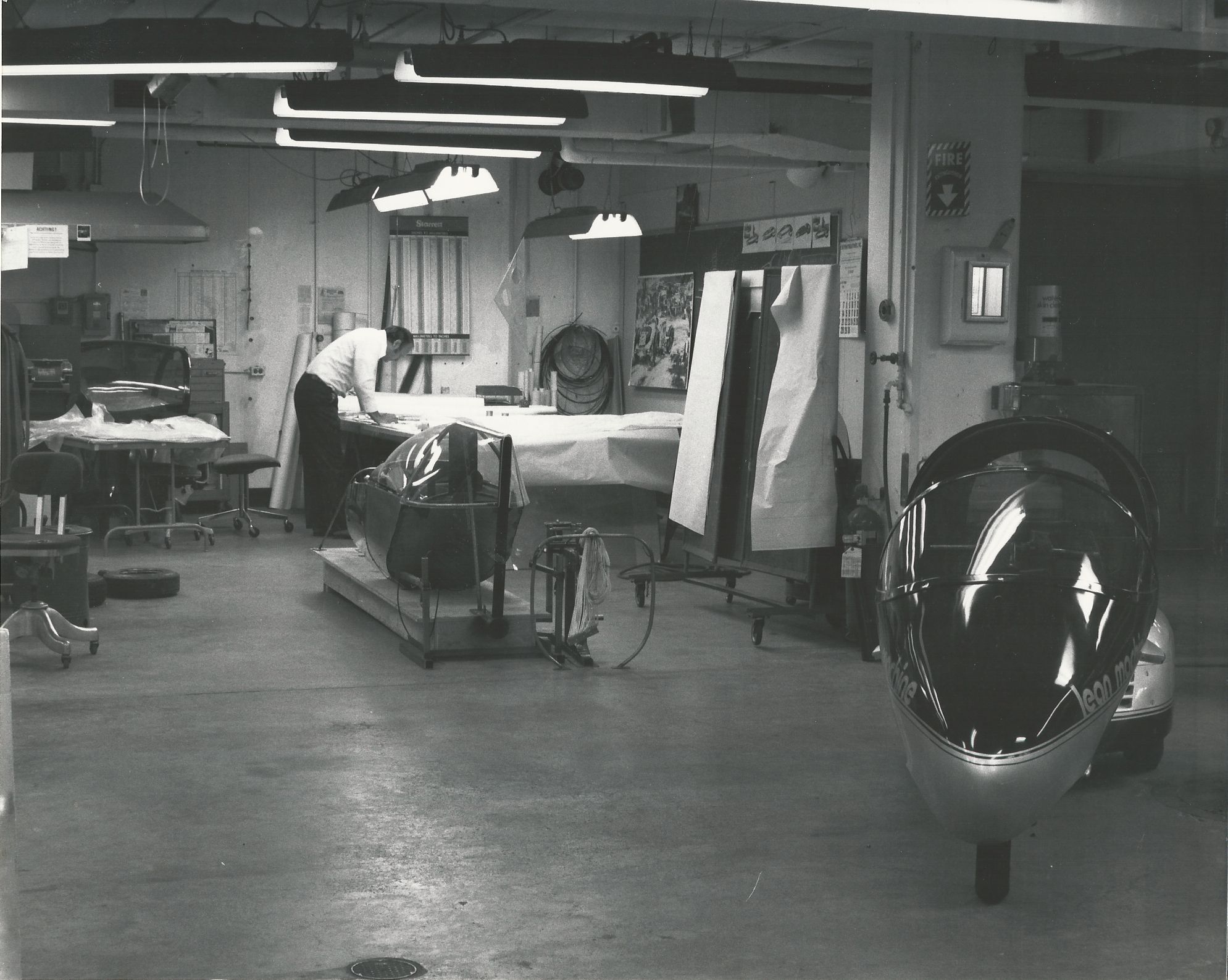

As the design progressed, Winchell and his team switched the three-wheeler to rear-wheel drive but ultimately kept the foot controls for tilting. They then brought in GM design staff to start laboring on the vehicle’s appearance, with some early drafts taking cues from the XP-511 three-wheeler that GM toyed around with in the late Sixties. As seen in the photo below, it’s small, with a wheelbase of just 71 inches and with minibike front and boat trailer rear tires.

Photos courtesy Nick Gigante.

At least three Lean Machines made it out to the public, according to Gigante. The one that debuted at Epcot’s GM World of Motion display, identified by its narrow Kamm tail, was a non-runner for display purposes only and could theoretically return 200 miles per gallon. The aluminum-bodied one that appeared in most of the press photos and videos with the wider Kamm tail had a 15hp engine in the non-tilting rear section that delivered a top speed of 80 mph and mileage of around 120 miles per gallon. (According to Egan, it was a pull-start 185 cc engine from a Honda ATV, backed by a five-speed semi-automatic transmission and Peerless garden tractor differential, that powered the Lean Machine). Meanwhile, a third wide-tail Lean Machine had a 39 hp engine that allowed the Lean Machine a little higher top speed (100 mph). While the Epcot narrow-tail version had a 0.15 coefficient of drag, the working versions had a chunkier 0.35 cD – not the lowest cD in a concept vehicle, but Winchell said the Lean Machine more than made up for that by its smaller frontal cross section.

Winchell retired in the spring of 1982, a few months before the Lean Machine’s debut, though he appeared in many an interview about the vehicle. It wasn’t quite his last accomplishment at GM, according to Gigante – he also worked on a Loran-based pre-GPS computerized navigation system and an interior-mounted side-view mirror that eliminated blind spots – but it was probably the last to be seen by the general public.

While GM had the basic premise of the Lean Machine down, production plans never materialized. Ironically, that was probably in part due to the company’s downsizing programs over the prior few years, including the X-body cars, GM’s first to utilize the transverse-engine front-wheel-drive plan that Winchell advocated for 20 years prior.

As for the various prototypes and Lean Machines, Winchell passed on the non-powered and one of the powered scooters to Gigante. One of the two wide-tail Lean Machines went on to appear briefly as Wesley Snipes’s ride in the 1993 movie “Demolition Man,” along with several other GM concept vehicles, thus qualifying it for the Petersen Automotive Museum’s recent sci-fi movie cars exhibit. It’s scheduled to return to the GM Heritage Center sometime this month, Gigante said.

SOURCE: Hemmings