History of Automotive Design: J.T. Cantrell & Company

By Walt Gosden

- Apr 14, 2020

The Cantrell factory in Huntington, New York, in the 1940s.

Builders of wood-sided Suburban bodies

Station wagons, also known as depot wagons or depot hacks, give an accurate depiction of the body style and function of the vehicle they represent. Horse-drawn wagons were used to deliver people to train stations and depots before the invention of the motor car. Almost immediately upon its invention, the automobile would see commercial application for businesses that needed to move products, goods, and people. Station wagons would shuttle people and their luggage primarily between hotels and train stations, but it was soon realized that they could also be useful to transport goods and larger families and their belongings much easier than a less spacious car.

One of the most prolific builders of station wagon bodies was J.T. Cantrell & Company of Huntington, Long Island, New York. As a successful iron worker, carriage maker, and boat designer and builder, Joseph T. Cantrell adapted his business and skills to become a premier designer and "maker of Suburban bodies," which we now view as the wooden-bodied station wagon. In all the company's advertising up through the early 1930s, it never referred to its coachwork as a station wagon, but always as a suburban body. But, as other manufacturers came on the scene, Cantrell started to call its offerings "station wagons" by the late 1930s.

This photograph of Joseph Cantrell (left) and his brother Albert (far right) was taken outside the office at the Cantrell factory on Long Island.

Cantrell, the man, was born on the north shore of Long Island in 1875, one of 13 children. When he was 13 years old, he relocated 10 miles west to Huntington to attend school and learn a trade. He then worked in carriage building factories close to New York City, and one in Bridgeport, Connecticut. He used a sailboat to cross Long Island Sound to get to Connecticut, returning home to Huntington on weekends.

In 1905, when he was 30 years old, he purchased Scudder's blacksmith shop and carriage stand at 250 Main Street in Huntington; a bank building is currently located there. In 1909, Cantrell moved that carriage business to nearby 16 Wall Street. By 1913, his younger brother Albert joined the business. Two years later, the company had transitioned from manufacturing horse-drawn carriage bodies to designing and constructing coachwork for cars, which became its primary business for the next 35-plus years. It was at this point the name was established as J.T. Cantrell & Company.

The field next to the Cantrell factory was full of rear body sections removed from Chevrolet two-door sedans. After the cars were shipped from the Chevrolet plant in Tarrytown, New York, Cantrell removed what was not needed. It was the most economical way to obtain what the manufacturer required, as well as have a driving, moveable platform.

Cantrell specialized in depot wagons made of wood. Truck chassis, at the time, were too large and more awkward to drive, thus a compromise to have a vehicle with a body to easily accommodate people was invented. Cantrell's first bodies were not station wagons, but cab and box type for the Primene Baking Powder Co.

The main production of suburban bodies that Cantrell built were mounted on Dodge, Ford, and Chevrolet chassis, as they were the most popular and easily available on Long Island. The Chevrolet chassis were driven down from Tarrytown, where the Chevrolet factory was. This was quite a trip in the early post-World War I era, as many of the bridges we have now did not exist. Ferry service across Long Island Sound was extensive, departing from numerous locations in Westchester County. Dodge chassis were shipped directly by rail from Detroit.

Albert Cantrell with one of the company's earliest efforts, several decades after it was designed and built.

It would be nearly a decade later when a suburban/station wagon would find favor with wealthier clientele for use on their estates, thus more fashionable and expensive chassis would be ordered to have wood wagon bodies fitted. These automobile chassis were obtained directly from the factory or from local car dealerships. The customer would go to the local dealer, order a new car, then, upon delivery, drive the car to Cantrell.

In the shop, the new factory body would be removed aft of the front door posts, yet Cantrell would try to use most of the original body, including the cowl, windshield, and sunvisor area; this practice continued up until WWII.

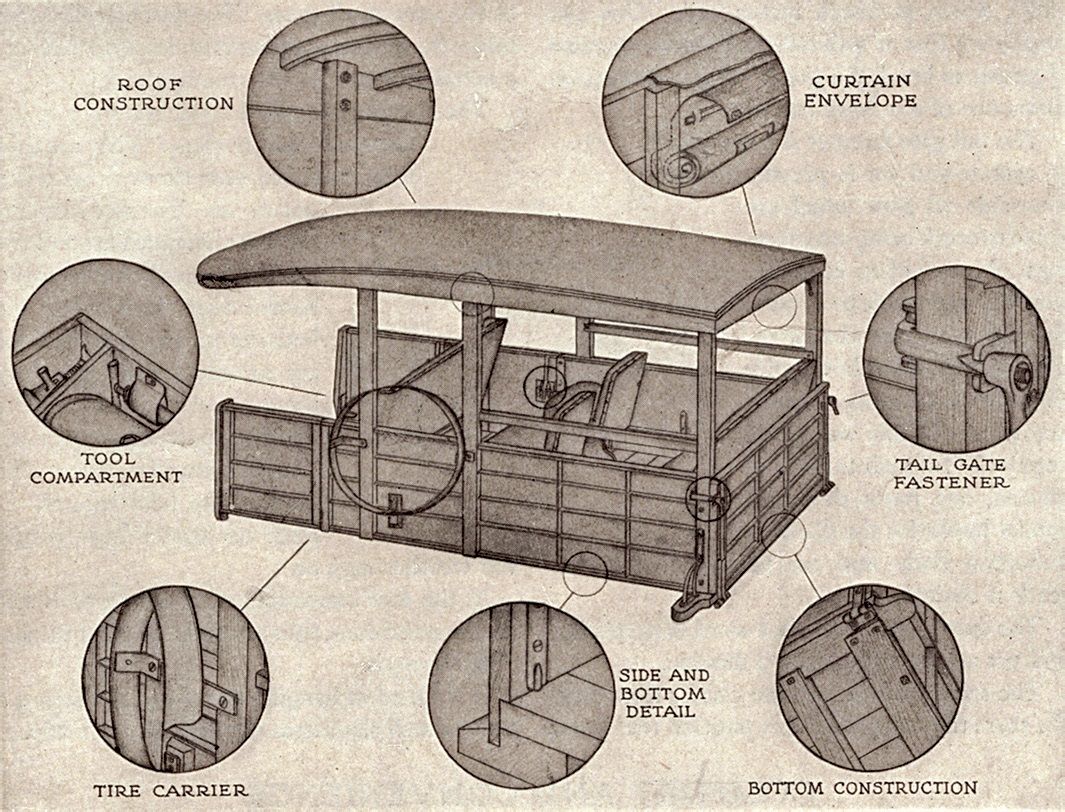

Details of the suburban bodies from the mid-1920s showing "exclusive features covered by U.S. Patents."

As Cantrell's business expanded, in 1925, a new plant was built and opened south of the village of Huntington on McCay Road, with the Long Island Railroad tracks along one side of the property. This was an enormous advantage to the business as the railroad siding allowed chassis, complete with cowl and fenders, to be delivered directly to the factory. By about 1930, Cantrell employed 35-40 people; in later years, the company employed nearly 150. Besides bodies, it also made all the iron brackets, braces, tire carriers, and other metal hardware required to assemble them.

When Cantrell started to receive larger orders for its suburbans, many auto manufacturers had contracted with it to supply the station wagon bodies featured in the Cantrell sales literature.

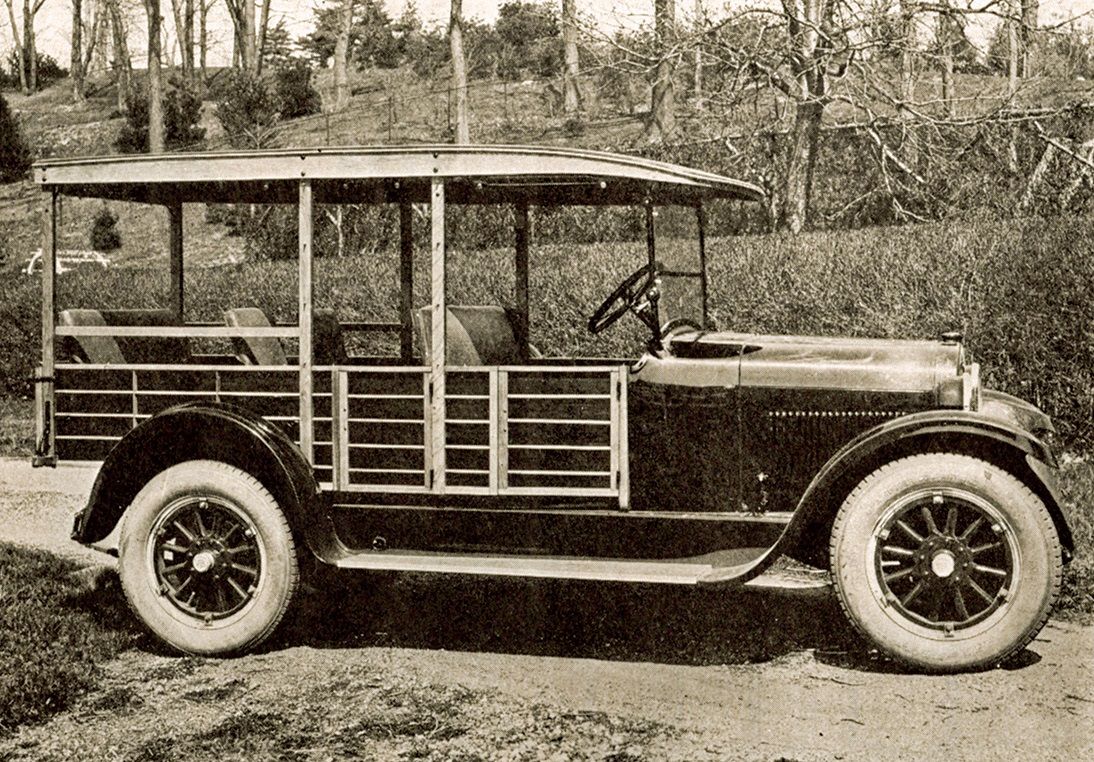

The Dodge Brothers chassis circa 1926 used a touring-model cowl and windshield, as well as hood and fenders.

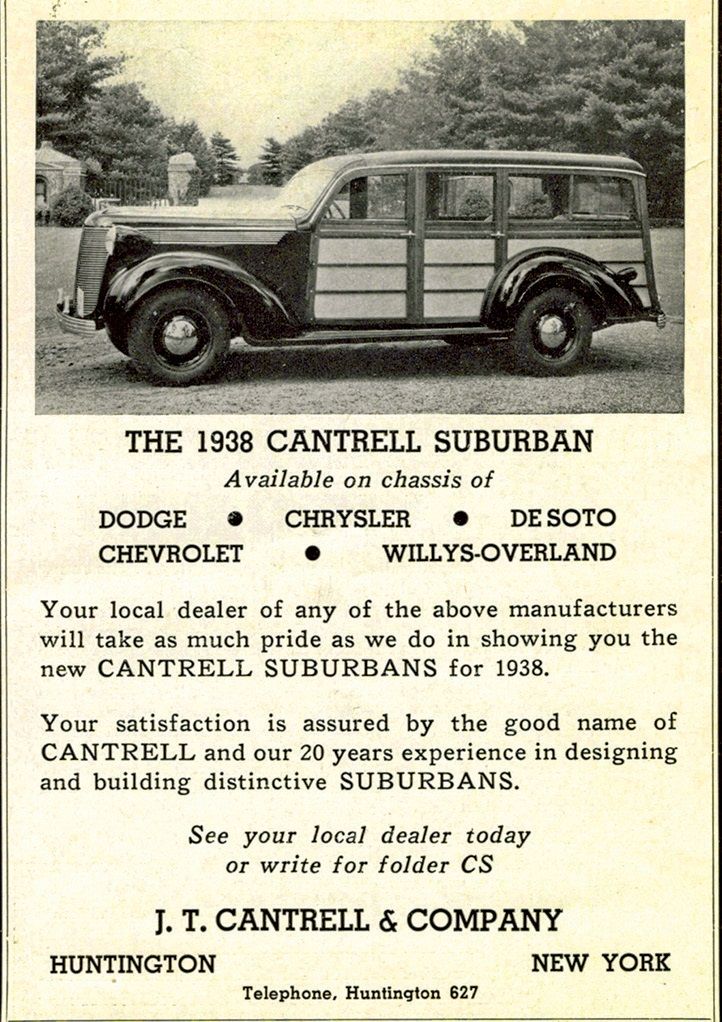

According to customer orders, by the late 1920s, larger car chassis, such as Franklin, Buick, Cadillac, and Pierce- Arrow, were being used. These requests were generated by advertisements that Cantrell placed in society periodicals, including Country Life and National Sportsman. The ads stated: "Your satisfaction is assured by the good name of CANTRELL and our 20 years experience in designing and building distinctive SUBURBANS."

This decal was affixed to the interior door post on Cantrell bodies to identify them once they were completed.

By 1937, Cantrell was regularly building bodies on Chrysler, De Soto, Chevrolet, Dodge, and Willys-Overland chassis; bodies on Fargo and De Soto chassis were exported to Europe as complete cars. Each body featured a metal tag: "J.T. Cantrell & Co. Body Builders, Huntington, N.Y." Cantrell also held design patents for many of the components it created, such as Patent No. 1417140 for its cast metal spare tire holder.

Business thrived and, during its peak production years in the 1920s, Cantrell was producing 10 station wagons per day to meet demand. All bodies were built by hand with minimal or no assembly-line machinery to assist production. The body side panels were made of walnut and had a dark color in contrast to the wood used to frame the body, such as doors, tailgate (called a tail board by Cantrell), and roof. The body sills, frame, top rail, door posts, sub sills, and tail board were made of oak or ash. The tail board had special hooks to keep it in place, but many customers used chains to support the tailgate when lowered. A tool compartment was located under the front seat, "which makes it unnecessary to carry a toolbox on the running board," stated Cantrell.

Floors were covered in linoleum and seats upholstered in a dark mottled blue water-resistant material. The curtains in the rear quarter panel window area were black waterproof material, as was the curtain above the tailgate; they were made of imitation Spanish leather. The curtains rolled up inside the top rail above the rear quarter windows and were enclosed in an envelope made of the same material. When not in use, this allowed them to be fully protected from the effects of the sun. The bottoms of the side curtains were wrapped to keep out all drafts, as well as water. In the 1920s, Cantrell provided a printed account of how this was done, to its perspective customers in sales brochures. "The curtains are held securely in place no matter how rough the weather may be."

Cantrell promised that the passengers were accommodated with great care with seats made as comfortable as possible. "All seats were reinforced with springs and stuffed with real curled hair." The middle and rear seats were removable, and the rear seat could be moved to the center of the car between the rear doors to allow extra room at the back for packages, but also to "carry several dogs or, on the return from camp, a large quantity of game." They also noted that "stains will not harm a suburban body."

By 1927, Cantrell was promoting its bodies mounted on Dodge Brothers chassis and issued promotional material specific to the Dodge: "The Cantrell Suburban Body for the Dodge Brothers chassis was designed not only for the work required of it, but also with an eye to its appearance."

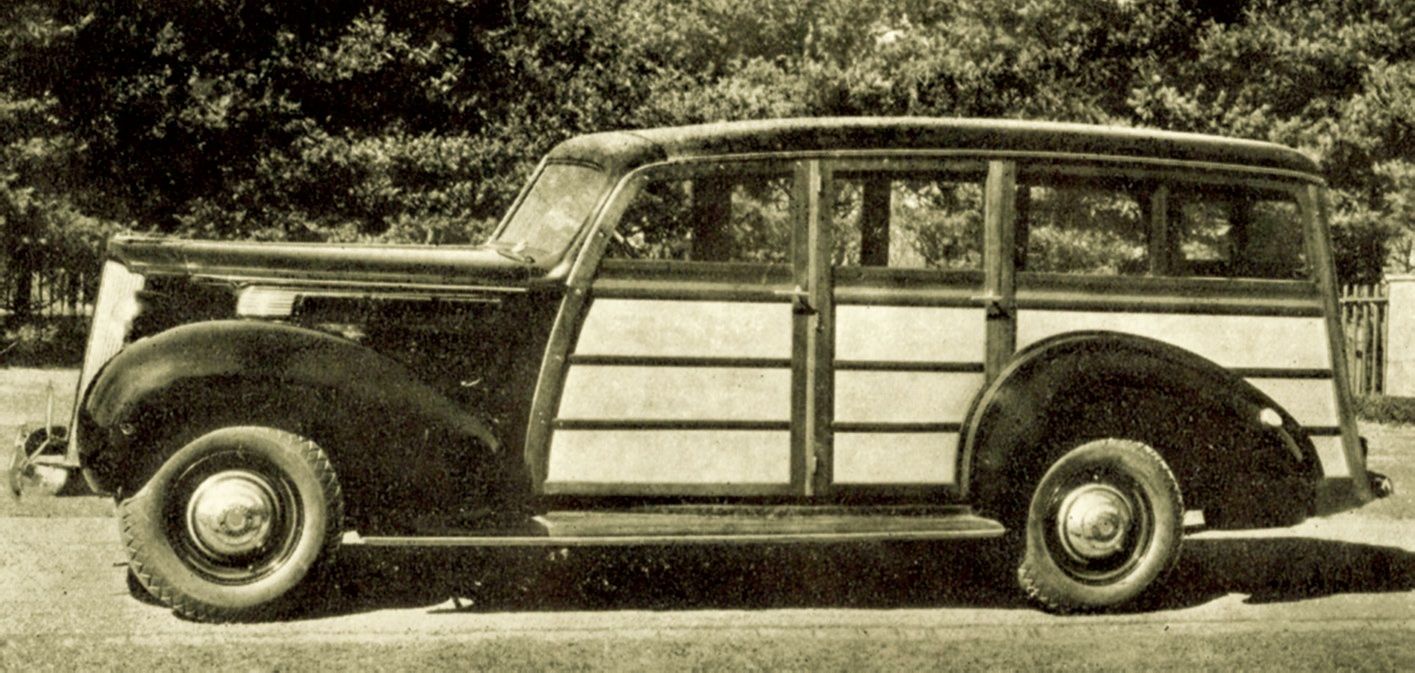

By 1938, Packard chassis in both Six and Eight series models started to be used. Cantrell announced that white maple with mahogany trim was used for the visual effect of contrasting woods, along with extra coats of "the best long wearing varnish," which made Cantrell's work stand out from ordinary station wagons. Safety glass was now being used for all windows.

The seat material was still a heavy-duty leatherette, now brown in color to better harmonize with the natural color of the wood. Rear and center seats continued to be interchangeable to accommodate larger loads as needed. Rubber matting for floor covering, maroon in color, replaced the linoleum of previous builds. Covered chains to support the tailgate were now standard equipment, and the spare tire for six-cylinder Packards was mounted through the floor, while the eight-cylinder Packard's spare was in the front fender.

For the remainder of the late 1930s until World War II, Packard was promoted by Cantrell in its advertising folders, stating that the bodies had "truck space with car comfort" and that there was "no need to sacrifice smartness for utility."

In 1938-'39, Packard Six (models 1600 and 1700) and Eight (models 1700 and 1701) chassis were fitted with Cantrell station wagon bodies. Promotional brochures were printed specific to that body style by Cantrell for 1938 and by Packard for 1939.

The Cantrell patented design of its station wagons continued with "a mahogany structure with fi nest white maple panels." The front seat was now adjustable by 4 inches to provide the most comfort for the assorted heights of the drivers. Special orders for wagon bodies built to meet the individual needs of a customer were still being accepted, and a small number of custom-equipped wagons were built as well. This was especially true of local customers from the nearby large estates on Long Island's wealthy North Shore.

Five different makes of chassis were readily available with no special effort having to be made in 1938; seen here is a De Soto. Cantrell had developed a good relationship with Chrysler Corporation, so its station wagons were easily ordered through Chrysler's network of dealerships.

Just about anything could be designed to meet a customer's wishes, including special tailgates to allow hunting dogs to enter and exit and space for ammunition boxes; everything was taken into consideration and provided for by request. The personnel who worked for the estates did not have to travel any great distance to see that the specific requests were being built to precise instructions.

After WWII, Cantrell continued in business, but most of the chassis that received its station wagon bodies were on Dodge "Job-Rated" ½-ton B-108 truck chassis and Studebaker truck chassis. For those who wanted their wagon built atop a Dodge chassis, they had to place an order with the Dodge Distribution Department for the B-108 cowl-windshield chassis "in the regular manner" with instructions to ship to Cantrell; at the same time, the order for the new wood body would have to be placed with Cantrell.

The bodies, in 1948, were constructed of ash for the frame structure with panels of Marine-type mahogany plywood. Individual side panels were now being used to simplify replacement in case of damage. As with pre-WWII bodies, the exterior wood pieces exposed to the elements were joined with water-resistant glue and "every piece of wood was submerged in toxic wood primer as a precaution against dry rot, fungus and insect attack." Three double-coats of oven-baked spar varnish were used to coat the wood body.

In 1950, Joseph Cantrell retired at age 75 and turned the business over to his brother and long-term partner Albert. By 1958, the firm ceased operations. All-metal station wagons had become very popular with the many new families that appeared on the scene after WWII. Metal wagons also gained popularity, because they didn't require any maintenance, unlike what the wood-bodied wagons needed. No one wanted to sand and revarnish the wood body of their car every year if the car was in constant use all year round.

In 1949, the Studebaker truck chassis also provided a platform to receive Cantrell station wagon bodies, which now featured an updated body design.

SOURCE: HEMMINGS