After recent Pierce-Arrow Society ruling, car clubs given some control over fates of resurrected brands

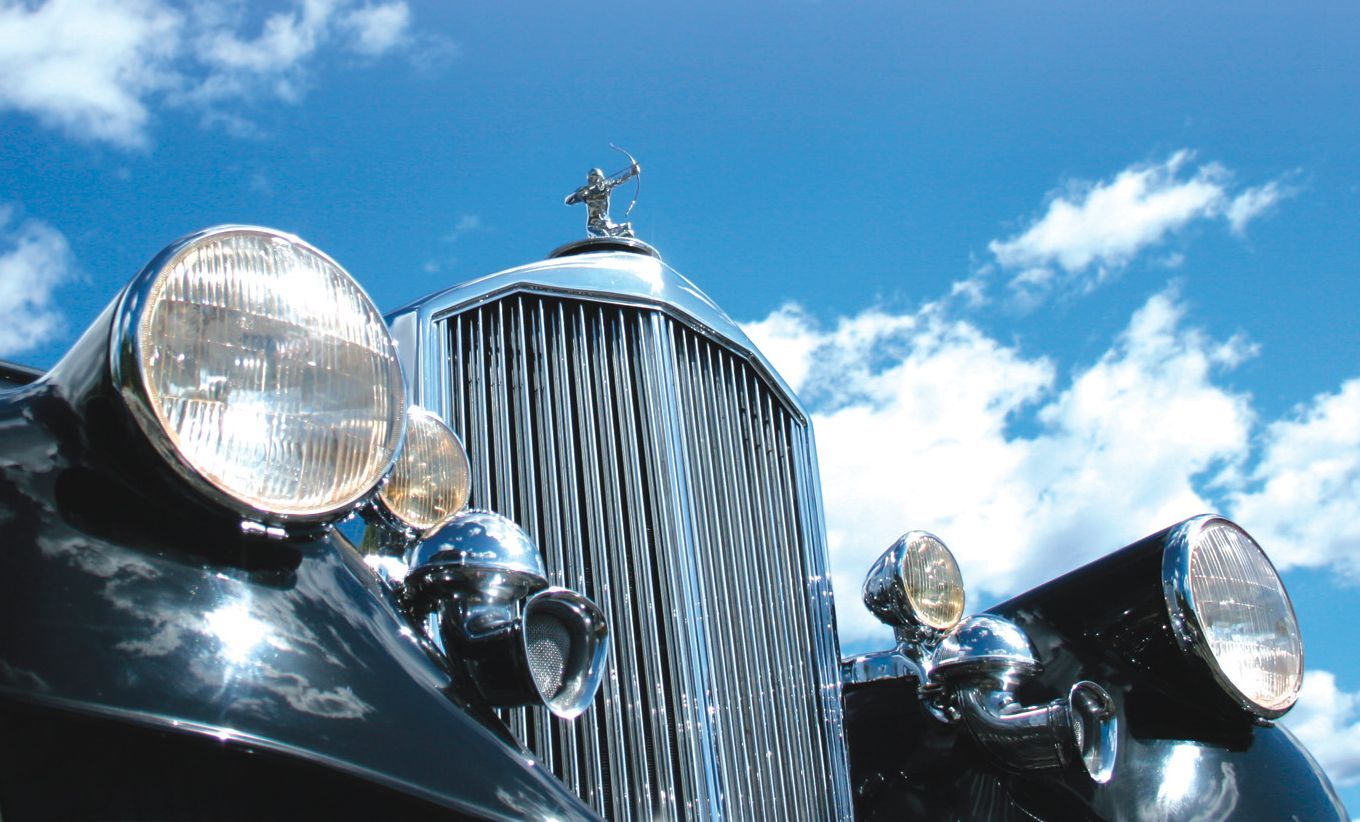

Photo by the author.

In the annals of automotive history lie the names of thousands of dead carmakers. While most of them remain long-forgotten, some still carry enough cachet for occasional attempts at reviving those brands. Or, at least, that was the case until a recent U.S. Patent and Trademark Office ruling that effectively put the fates of defunct brands into the hands of the car clubs dedicated to those brands.

“We’re delighted; it just makes good sense,” said Marc Hamburger, a former president of the Pierce-Arrow Society who pursued a recent trademark case to defend the Pierce-Arrow mark from use by modern-day car manufacturers. “You cannot make a new Pierce-Arrow. They were built from 1901 to 1938, period.”

The dispute over the Pierce-Arrow trademark dates to January 2015, when the Pierce-Arrow Society’s outside attorney, Alan Cooper, discovered that William Greene, the president of filtration company SpinTek, had filed for a trademark on the Pierce-Arrow name for use in automobile production. The name was reportedly slated for the Millennium Golden Dragon, a customized stretch limousine based on a modern Bentley, as seen in a promotional video.

“It had nothing to do with Pierce-Arrow,” Hamburger said.

In response, the Pierce-Arrow Society, via Cooper, filed an opposition to Greene’s trademark with the United Stated Patent and Trademark Office, claiming that Greene’s trademark violated the collective membership mark – a type of trademark – that the Pierce-Arrow Society has held since the late Fifties.

As detailed in the opposition, the Pierce-Arrow Society claimed that Greene’s trademark falsely suggested a connection between Greene’s limousine and the Pierce-Arrow Society and that it likely caused confusion between the two trademarks. While the Pierce-Arrow Society does not hold the rights to the Pierce-Arrow name or claim to be a legal successor to the Pierce-Arrow Motor Car Company, the Pierce-Arrow Society argued in its opposition that “it is the de facto successor to The Pierce-Arrow Motor Car Company with respect to the preservation of the memory of the antique Pierce-Arrow automobiles… and the protection of the Pierce-Arrow mark.”

The USPTO’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, after hearing the case, released its decision late last year, agreeing in part with the Pierce Arrow Society. Because the Pierce-Arrow Society did not have the actual rights to the Pierce-Arrow name (“whatever rights the defunct entity had were extinguished when it went bankrupt and ceased to exist,” the TTAB noted) and because the Pierce-Arrow Society failed to establish any sort of fame or reputation, the TTAB dismissed the Pierce-Arrow Society’s claim that Greene’s trademark suggested a false connection.

However, the TTAB did agree with the Pierce-Arrow Society’s likelihood of confusion claim, noting that potential customers might mistakenly believe that the Pierce-Arrow Society in some way endorsed or in some way influenced the Pierce-Arrow automobiles Greene had planned to build.

"There is an explicit and complementary relationship between automobiles and automobile clubs for the very same brand of automobiles. In this case, the Pierce-Arrow Society is a collective membership organization for people who have an interest in preserving and fostering interest in Pierce-Arrow automobiles. Relevant persons would be likely to assume a connection or affiliation with or sponsorship by the owner of the automobile trademark if a trademark for an automobile is used as, or as part of, a collective mark indicating membership in an automobile club."

Thus, the TTAB ultimately sided with the Pierce-Arrow Society and rescinded Greene’s trademark. According to Cooper, Greene briefly considered appealing the TTAB’s decision, but later withdrew that appeal, effectively bringing the case to an end.

In addition to ruling in favor of the Pierce-Arrow Society, the TTAB determined the decision to be precedential, meaning other car clubs could potentially refer to the decision in their own oppositions to trademarks for other revived automobile brands. Cooper cautioned, though, that while the TTAB’s decision “provides a significant basis for car clubs to protect trademark rights,” referring to the case’s precedent would only work for similar or analogous situations.

Whether the TTAB’s ruling would throw water on the fire for plans to build turnkey replica vehicles under the Low Volume Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Act remains to be seen and will likely depend on individual circumstances. Under the replica car act, replica car manufacturers have to obtain “license for the product configuration, trade dress, trademark, or patent, for the motor vehicle that is intended to be replicated from the original manufacturer, its successors or assignees, or current owner of such product configuration.”

Indeed, many, if not all of the manufacturers who are or were planning to take advantage of the replica car law had already secured the rights to the vehicles’ trademarks. Craig Corbell, for instance, bought the rights to the Cord name for $242,000 in late 2014 from the family of the late Glenn Pray, who had previously bought the rights from a Cord company successor, for his planned Cord revival project.

Hamburger, whose career focused largely on protecting Coca-Cola’s trademark from dilution, took a more expansive view of the TTAB decision’s implications. “I wish other clubs would take more steps to protect their trademarks,” he said. “The cars live on; I hate to call them dead brands because the cars are still on the road, still used.” He maintains that Corbell – as well as the current holder of the Cord rights following Corbell’s decision to sell them at auction – shouldn’t have been able to even entertain a Cord revival project.

According to Hamburger, the Pierce-Arrow Society’s opposition to the trademark didn’t arise from any value judgement over Greene’s attempt to revive the name. Rather, the club opposes any and all attempts to revive the name. For example, it successfully prevented a group of European investors from using the name in an attempted revival more than a decade ago using a V-24 engine and a Luigi Colani-designed body. (In the United States, at least. In Canada, the Pierce-Arrow Society’s opposition to Olaf vom Heu’s registration of the Pierce-Arrow trademark was overruled.)

“It’s inconceivable that we’d ever endorse the creation of a new Pierce-Arrow,” he said.

SpinTek has registered two other automotive trademarks, one for Peerless and one for Berline. The latter has been abandoned, but the former remains valid and has gone unopposed.

Neither Greene nor his trademark attorney have returned calls for comment for this story.

SOURCE: HEMMINGS